In this published collection assembled in book form in 1895 - actually assembled many years after William Fothergill Cooke died, is found contained a forward by the now very aged Latimer Clark, the former dedicated former employee of Cooke's at the Electric Telegraph Company and co-founder of British based Institution of Electrical Engineers (IEE) and what is today IEEE.

In November of 1891, Latimer Clark donated to IEE the original manuscript letters of William Fothergill Cooke that Cooke had written to his mother between the years 1836 and 1839 describing and discussing his exploits, troubles and triumphs he endured on the path at developing and perfecting the first commercial digital electric telegraph communications system in the world.

The letters had been given by Cooke before he died to his son-in-law Colonel Andrewes to Latimer Clarke.

In turn, Colonel Andrewes presented the letters, of which only a portion are shown transcribed and presented this book, to Latimer Clark, who then provided same to IEE.

A carte-de-visite photograph of a young Cooke circa 1860, apparently being the only copy extant, was given personally by Cooke to Latimer Clark, and such is reproduced in this 1895 book through the Swan type process of that time.

As well, the last entry in this book is entitled: "Award of Sir Marc Isambard Brunel and Professor J. F. Daniel" and consists of the actual draft awarding equal credit to the invention of the electric telegraph in England to both Wm. F. Cooke and Charles Wheatstone.

Essentially, the bulk of this fascinating book reprints the content of the more interesting manuscript letters Cooke wrote between 1836 through 1839 to his mother describing his trials and tribulations along with his triumphs at developing the electric telegraph in England.

Curiously all of this is done including the dates and address locations of Cooke's changing residences, that as well, come to concretely document the circuitous path he travelled during this monumentous effort.

The second half of this book consists of a "Memior of Sir William Fothergill Cooke" by Latimer Clark. What is most significant is how Clark clearly outlines how Samuel F. B. Morse, through documented press stories of the day, had difficulty getting telegraph signals to go long distances and how, in 1838, had came to Europe and flat out "was refused a English patent on the ground of want of novelty."

Clarke also reveals the sentiment of the day, as relayed to him by Cooke before he died, that Samuel F. B. Morse had essentially copied the prior telegraph design methodology developed by "Messrs Cooke and Wheatstone and other European telegraphers and that there is no ground for that claim of priority which it has sometimes been endeavored to set up."

In a few of his earliest letters provided in the book, those from 1836, Cooke tells his mother of Moore, the clockmaker from Clerkenwell, who apparently made Cooke's first telegraph model after his arrival back in London from Heidelberg.

In one letter Cooke does mention having some difficulty with the work Moore produced. Into 1837 no mention is made of Moore as the machinist. By November 1837, we now hear Cooke bring up a new "very clever mechanician who has arranged with 4 or 5 good workmen to commence operations as soon as I give the word."

No mention in the letters found in this book cite Frederick A. Kerby by name, but from what is known from other extant written correspondence of Cooke's - he on many occasions referred to Kerby as his "mechanician;" i.e. the same "mechanician" mentioned by Cooke first in his 9 November 1837 letter to his mother.

All in all, this book is a fascinating link providing superior data on the early development of the telegraph and coupled with pages found in the newly discovered Cooke's manuscript journal / Codex Lipack - obviously expands upon the amazing story of Cooke's work and brings it further into a much more vivid context of observation and study.

However, since the book ends in late 1839, the details of the Blackwall Railway installation - the break through installation beginning in July of 1840 which marked the first true perfection of the basis of modern commercial digital electric communications in the world, is obviously absent.

BOOK REVIEWS

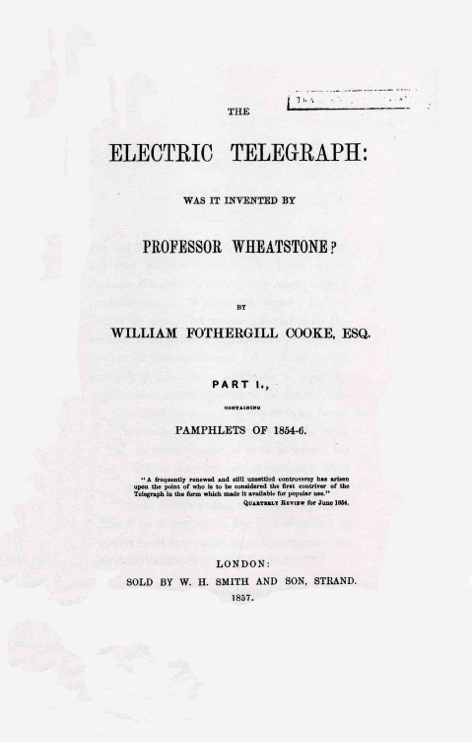

THE ELECTRIC TELEGRAPH - PART 1. William Fothergill Cooke, Esq., author. University of Michigan Library reprint from 1857 W. H. Smith & Son, Strand first edition cumulative reprint entitled: "Part 1 containing Pamphlets of 1854-56." 282 pages, illustrated.

The story behind the development of the Cooke and Wheatstone electric telegraph is brought forward by William Fothergill Cooke through the various letters he executed after the Arbitration case between himself and Wheatstone of 1840-1841 was settled. Cooke explains how the only actual instrument that was Wheatstone's creation was the "Permutating Key-board," which was included in the Cooke and Wheatstone 12 June 1837 English Patent held jointly by them. Cooke further explains that the "Permutating Key-board was the only real 'invention' Wheatstone contributed to the two's effort after the partnership between the two was initiated.

Cooke also explains how in March of 1836, while studying anatomy and anatomical model making at Heidelberg, he had witnessed Professor's Moncke's demonstration of the Pavel Schilling 1835 model telegraph and it was from here that he developed the vertical lever and 'make and break' action for the 1840 Blackwall Railway telegraph installation, which was the first perfected commercial application of telegraphy in the world. Most significantly the Blackwall Railway installation is the primary thrust of Cooke's telegraph manuscript journal / Codex Lipack.

It is Codex Lipack that opens the doors to further study and understanding of exactly just how Cooke developed and perfected the telegraph with the Blackwall Railway installation by allowing both today's student and academic professor alike to examine and compare the details found in Cooke's writing in this University of Michigan reprint of Cooke's 19th century written accounts together with the actual writings and drawings found in Cooke's 19th manuscript journal / Codex Lipack.

The great American inventor Thomas A. Edison never went to the extremes that Cooke has done in documenting his own work. Cooke was extremely articulate and methodical in documenting his work on the telegraph. Thus, because of this arduous effort on Cooke's part, today such efforts can be studied in a most profuse and detailed manner unlike that has been done ever before in the realm of invention. Studying the Cooke and Wheatstone patents do not tell the whole story, as they only show end results.

Cooke also discusses in great depth how what he learned at Heidelberg following the principles of Schilling during the Moncke March 1836 lecture, paved the way for him to invent and perfect the 'Alarum' or 'telegraph alarm.' The drawings found in Cooke's journal / Codex Lipack clearly reveal a number early annotated drawings of the Cooke Alarum, including even one found in the Cooke and Wheatstone 12 June 1837 patent! What Cooke brought up at the 1840-1841 Arbitration between himself and Wheatstone regarding his proprietary and sole rights as to inventing the Alarum is clearly and irrefutably revealed in the Cooke telegraph manuscript journal / Codex Lipack.

As scholars hopefully come to study Cooke's work as found in his manuscript telegraph journal, and cross-reference this "Part 1" of his letters, and also in following, that of "Part 2" - much more knowledge and insight about this important time in modern man's present epoch of technological development will assuredly come forward.

Only a small inkling of discovery can be provided here at WilliamFothergillCooke.com because it is too numerous to encapsulate here.

Thus, much much more awaits the scholar of electrical history in the future.

THE ELECTRIC TELEGRAPH - PART 2. William Fothergill Cooke, Esq., author. University of Michigan Library reprint from 1856 W. H. Smith & Son, Strand first edition publication of "Part 2 containing Arbitration Papers and Drawings." 268 pages, illustrated.

This book provides detailed accounts by Cooke through the statements he made in 1840 during the Arbitration hearing between himself and Wheatstone before the arbitrators.

Cooke also explains how it was on 6 March of 1836, while studying anatomy and anatomical model making at Heidelberg, he had witnessed Professor's Moncke's demonstration of the Pavel Schilling 1835 model telegraph. Shortly thereafter, Cooke explains how he started to make his first telegraph, partly at Heidelberg and then finishing it at Frankfort - before he brought it with him when he returned to London, where he showed it to Michael Faraday. It was Faraday who suggested Cooke call upon Professor Charles Wheatstone at King's College, London.

Cooke explains also in this account of the Arbitration proceedings, that it was following the examination of the 1835 Pavel Schilling telegraph model presented by Prof. Moncke at Heidelberg in 1836, that he developed his design for a galvanometer. It is the design of which that is the primary basis of the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph system brought forward following the combined efforts following the formation of the Cooke and Wheatstone partnership in "May of of 1837." Significantly, in the Cooke manuscript telegraph journal / Codex Lipack, there are a number of drawings of the Cooke galvanometer, including that identified with the word "Galvanometer" - all executed by Cooke in his own hand. There is even a drawing of a galvanometer executed in two colors of ink.

Several discussions of Cooke using the expertise of machinist Frederick A. Kerby during the construction of the telegraph instruments for Cooke and Wheatstone are provided in this "Part 2" volume as well. It was Kerby who also was Cooke's primary witness during the Cooke and Wheatstone arbitration.

Cooke also discusses in great depth how his perfection of the 'Alarum' or 'telegraph alarm,' all as far back as his time in 1836, at Heidelberg. Several drawings found in the Cooke journal / Codex Lipack clearly support what is shown stated during the Arbitration between himself and Wheatstone regarding Cooke's proprietary and sole rights at inventing the Alarum.

Other discussions delve deep into the Great Western Railway telegraph installation of 1838 - which is mentioned in Cooke's telegraph manuscript journal / Codex Lipack. Also, the prior work executed during the earlier Liverpool and Manchester Railway telegraph trial demonstration is provided in this "Part 2" volume reprint.

Discussion also treats the London and Birmingham Railway line telegraph installation telegraph trial that Cooke was also instrumental in mounting.

As scholars hopefully come to study Cooke's work as found in his manuscript telegraph journal, and cross-reference this "Part 2" of the Arbitration proceedings, together with "Part 1" of Cooke's The Electric Telegraph - again, much more knowledge and insight about this important time in modern man's present epoch of technological development is bound to become wholly manifest as well in adding to the breadth of knowledge currently lacking. It is this great lack of understanding that was even asserted to and identified by former Curator of Communications at the Science Museum, London - as found in his 2007 onwards paper and lecture for the Newcomen Society in past times.

The Blackwall Railway, discussed in this "Part 2," is, according to former curator Liffen also is a major void when it comes to how the telegraph was developed in the United Kingdom. The new knowledge gleaned from Cooke's telegraph manuscript journal / Codex Lipack provided here at WilliamFothergillCooke.com will become largely very significant as scholars begin to embrace this newly discovered work and study it in greater detail. Cross-referencing between the contents found in the Cooke journal with that of Cooke's published textual accounts and the various publisher patents will open up new and wider avenues of study that will lead to even more avenues of study and greater understanding as a whole.

Thus, much much more awaits the scholar of electrical history in the future. Understanding more clearly all of what the Arbitration was actually all about will become much more profound by studying Cooke's long lost but newly discovered telegraph journal work.

AUTHORSHIP OF THE PRACTICAL ELECTRIC TELEGRAPH OF GREAT BRITAIN. Thomas Fothergill Cooke, author. Forgotten Books 2012 reprint from the following first editons: 1856 W. H. Smith & Son, Strand, London publication and the 1868 R. E. Peach, Bath - Simpkin, Marshall & Hall, Stationers Hall Court, London publication, 131 pages, illustrated.

This book provides detailed published newspaper accounts from 1866 by the British news and press organizations detailing the ramifications about why Cooke was the true inventor of the perfected electric telegraph over that Wheatstone. The book also goes deep in the Arbitration hearing between Cooke and Wheatstone beyond 1840 and addresses the actions that arose in greater detail. Cooke's brother the Reverend Thomas Fothergill Cooke expended great effort in gathering and chronicling all of the more recent published accounts from 1866 and brought them forward in this 1868 publication.

Reading all of these accounts is absolutely fascinating and more remarkable

insight into Cooke's most intrepid efforts at perfecting the first commercial electric means of communication is brought fourth. This effort becomes even more profound when one actually is able to look at, see and study the plethora of evidence found in the Cooke telegraph manuscript journal / Codex Lipack.

What can become gleaned from Cooke's telegraph manuscript journal / Codex Lipack clearly will provide more light in the dark tunnel of knowledge and historical misconceptions handed down by previous scholars the world over - over the past century and half of time span and finally set the record straight - as Cooke obviously was hell bent on doing during his lifetime.

Once the pages of the Cooke telegraph manuscript journal / Codex Lipack can be scrutinized in greater depth by the world's scholars, much more appreciation of Cooke's sincerity about why he thought he was cheated by Wheatstone and also about why he felt he was indeed the true inventor of the telegraph will be universally more clearly understood.

This is of course, once the newly discovered work by Cooke is studied closely and more acutely in the future.

With the discovery of Cooke's journal and dissemination of its contents, all histories on the electric telegraph written by the world's scholars over the last century have become defective, incomplete and in time, essentially obsolete; remaining as only a rudimentary and basic guide to the full understanding that Cooke's journal yields.

Thus, much much more awaits the academic world regarding the true story behind the development and perfection of electric communications and its early days - together with its place today in modern times.

The International Journal for the History of Engineering & Technology - Formerly Transactions of the Newcomen Society, "Correspondence" by journal editor Roger Cline. Science Museum, LONDON, U.K. Vol. 83, No. 1, Jan. 2013, 145.

Article discussing letter from Dr. Thomas Biddle Perera to journal editor Roger Cline formally announcing the discovery by American historian and archivist Richard Warren Lipack of William Fothergill Cooke's telegraph builder's manuscript journal.

In this article, the Cooke manuscript journal discovery made in America is finally acknowledged in the United Kingdom; under the auspice of the century old Newcomen Society monicker. This represents the first printed international world announcement of the Cooke manuscript discovery outside of the United States of America. The first international Internet announcement was made on the W1TP

Internet virtual Telegraph and Radio museums website in 2011. This was followed-up by a full discourse of the discovery on the IEEE / Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers organization Internet website in 2013.

The Newcomen Society published discourse describes the discovery of the scrapbook and how the Cooke journal pages were found covered with 19th century news print clippings and engravings, and also describes the ultimate authentication of the Cooke journal itself. The letter Dr. Perera wrote to Newcomen society journal editor Roger Cline is heavily quoted and drawn upon. A full page of the prestigious international society journal is devoted to the discovery of the long lost Cooke work.

Line cut from back cover -

Codes Cyphers & Other Cryptic & Clandestine Communication making & breaking secret messages from hieroglyphs to the internet. By Fred B. Wixon. Black Dog and Leventhal Publishers, Inc., New York, NY - 1998, 704 pages, illustrated.

This voluminous book covers every imaginable type and form of cypher / code communications imaginable ever developed.

The dust jacket front cover flap succinctly states it all;

"Codes & Cyphers & Other Cryptic & Clandestine Communications chronicles the world of secret communication from hieroglyphic to the internet. The making and braking of codes through history has won or oct wars, exposed political intrigue, disguised secret religions, and secured financial transactions. It is a fascinating world of technological advances, cloak and dagger maneuvers and

war espionage."

The book covers everything imaginable that has do do with cypher and code whether it be of the static readable form, presented by mechanical means or transmitted by a variety of methods, including mainly by electronic means.

The work by Cooke and Wheatstone is discussed through-out the book. What is most significant is that all of the mechanical and mechanical / electronic means of producing cypher forms and sending cypher messages - for the most part, relies primarily on a 'wheeled' form of mechanism in a majority of the cypher / code instrumentation shown and discussed in the book - all inspired by the work found in the Cooke "ABC" dial telegraph - as found repeatedly in the recently discovered

Cooke telegraph builder' manuscript journal.

This book is very significant in that it tends to cover many aspects of a technology that is inherently embodied in the technological foundations originally devised, first developed and finally perfected commercially by William Fothergill Cooke - as found confirmed to have been developed by him first and clearly represented in his recently discovered manuscript work.

This book represents the first complete defense of this neglected scientist who was involved in the discovery of anesthesia, the electromagnetic telegraph, and the nature, location, and extent of copper deposits in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula - but all of which he was denied credit by unscrupulous people who profited instead by taking Jackson's input and capitalizing on it.

Among those was Samuel F. B. Morse, the America telegraph inventor.

Decrying Jackson’s diminished status in the history of American science, authors Richard J. Wolfe (formerly, Harvard University Countway Library of Medicine) and Prof. Richard Patterson (emer., Univerisity of California, Los Angeles) discuss that Jackson failed to come to his own defense by publishing nothing.

Such inaction in turn enabled Jackson's enemies to paint his counter claims ti their inventions or proclamations as unfounded. Worse yet Jackson was written off by his opponents as insane and an alcoholic. Jackson, the authors show, was born into privilege and was into the sciences for altruistic reasons. He was not driven by greed and thus pursued science for its own sake.

Most importantly, early on in 1832 onboard the ship "Sully" - while coming back from France where he had then just attended a symposium on electricity - that he came to meet Samuel Morse, who too was returning from France after studying masterwork paintings in the museums there. It was onboard the Sully that Jackson imparted to Morse the basic foundations of electro-magnetic telegraphy that caused Morse to became infatuated with it and lead him eventually to abandon his career as a painter.

The authors explain how Morse was not a true scientist but merely a technician fueled by mercenary considerations and greed.

America’s foremost physicist, Joseph Henry, whose work in the field of electro-magnetism also helped develop the telegraph, too did not receive any recognition for his work from Morse. The selfish Morse refused to give Henry credit and later went on to attack Henry and sought to unseat him as the Smithsonian Institution's first director when Henry challenged Morse's proprietary interest in the telegraph. The instance however was not burdened by public great controversy.

It was Henry that gave the idea of the electric relay to Charles Wheatstone when he visited Wheatstone in London; before Morse came along in 1838 after Henry's visit. It was here and then that Henry believed Morse learned of his relay, according to a holographic notation in Henry's hand later discovered and identified when found in a 19th century book on electricity and telegraphy.

Although this book on Charles Henry Jackson is laborious difficult to read in places, it is nevertheless a must in understanding how Charles Wheatstone and William F. Cooke's work, especially that of Cooke's as is exhibited in his own telegraph builder's manuscript journal / Codex Lipack, is pre-eminent in the realms of man's modern epoch.

Charles Thomas Jackson:

“The Head Behind The Hands." Applying Science To Implement Discovery And Invention In Early Nineteenth Century America. By Richard J. Wolfe & Richard Patterson, Norman Publishing, Inc. 417 pages. November 2007, Frontispiece, 8 plates and 4 illustrations.

Charles Thomas Jackson, a graduate of Boston's Harvard Medical College was a prominent Boston physician, geologist and chemist who was associated with three major inventions and discoveries of the first half of the 19th century in America.

Catalogue of the Wheeler Gift of Books, Pamphlets and Periodicals in the Library of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. Edited by William D. Weaver, member AIEE. With introduction, Descriptive and Critical Notes by Brother Potamian, Sc. D., Lond.,

Professor of Physics, Manhattan College. Reprinted by Martino Fine Books, (No date), Mansfield Centre, CT. Imprinted: "This Reprint is Strictly Limited to 150 Copies." Volume 1, 504 pages and Volume 2, 475 pages - bound into one. Profusely illustrated.

This amazing book chronicles up to 1909 basically the majority of every known book, pamphlet, periodical and printed matter ever published on electricity and telegraphy since the sciences first became sciences of study and implementation, inclusive to 1909.

This essential collection of printed paper on the developing science of electricity and telegraphy and history thereof was assembled by Latimer Clark of London. Latimer Clark not only was a major founder in 1884 of what today has become the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, but he was one of the earliest and most longstanding employees of William Fothergill Cooke and the Electric Telegraph Company shortly after its founding in 1845-1846.

Industrialist Schuyler Scatts Wheeler purchased the Latimer Clark electrical and telegraph book and paper collection in 1901 and donated it to AIEE. Wheeler was the co-founder, along with Francis B. Crocker of the Crocker - Wheeler Electric Motor Company of Ampere, NJ. This book of then collection is a catalogue of all of the items found in that collection at the time and those donated thereafter till 1909.

The book is a unlimited resource for learning of and knowing what was published and the date such publications occurred, with respect to electricity and telegraphy. It includes extremely early works on electricity by the earliest practitioners and many date into the 1600's.

One book included is that of Benjamin Franklin work with electricity and his electrical experiments, printed in England in 1751. Significantly, the earliest and most important electrical and telegraphy related works listed have their title pages reproduced as a full page in this 'Wheeler Gift' two volume work. The book cites 6377 titles comprising a total of 8179 volumes that were in the collection as of the year 1909.

An exhaustive work that is indispensable to any serious library or researcher in the field of electrical and / or telegraphic history.

FLEET FIRE - Thomas Edison and the Pioneers of the Electrical Revolution. By L. J. Davis. Arcade Publishing, New York, 2003. 350 pages.

FLEET FIRE is significant because it breaks away from the norm and doesn't embellish the name of Samuel F. B. Morse with undue praise, as Morse himself nevertheless would do during own his life time.

Morse clearly is shown to be a charlatan. The tome discusses the affair between Charles Thomas Jackson and Morse on the ship Sully in 1832, where Morse went on to claim the basics for telegraphy were all his.

The book amusingly also explains how Morse obtained a patent that made claim essentially how all electro-magnetic telegraphy applications, or so he on went to proclaim was based on his work. In the courts he won some legal infringement suits, such against the one against the telegraph developed by Royal E. House of Vermont, but eventually his arguments all collapsed under its own weight the year 1990 over time.

It was however the Morse code that prevailed for over a century and a half, and lasted as long as to the year 1990, as author L. J. Davis explains.

The book explains how Morse really did not know anything about electricity and significantly that he did not understand Ohm's Law. Author L. J. Davis also explains how William Fothergill Cooke did not understand Ohm's Law, and that both Morse and Cooke could not make a telegraph work past thirty feet because of a lack of an understanding of Ohn's Law and for lack of a electrical relay based on Ohm's principles.

But Cooke had Charles Wheatstone, and Wheatstone had talked to Joseph Henry - who was the benchmark to understanding electromagnetism. Morse did not know of Henry, but learned of his work after Morse went to England in 1838 and met with Wheatstone and saw the use of the electric relay and it arrangement found in the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraphy system.

This book is well written and shines a light on the various obstacles, forays and successes that brought forward what is today the world of electronics of which Cooke nevertheless was the first successful prolific practitioner to bring forward the medium on which today everything electrical is still based on in the realm of all things digital electric.

Telegraphic Railways: Or the Single Way Recommended by Safety, Economy, and Efficiency, Under the Safeguard and Control of the Electric Telegraph. By William Fothergill Cooke. This 1842 published first edition reprinted September 10, 2010 - Kessinger Publishing, LLC. 54 pages.

This book on telegraph railway usage obviously was prompted after William F. Cooke had come to mount his fight against Charles Wheatstone for equal credit at developing and perfecting the electric telegraph in England, particularly this first usage on the railways implementing safe regulation of train passage.

Since witnessing the Pavel Schilling telegraph demonstration under the auspice of Prof. Moncke while studying anatomical model making at Heidelberg, Germany - the idea of utilizing a perfected electric telegraph system for regulating safe train passage was solely the brainchild of William Fothergill Cooke and this publication produced in 1842, some years later clearly was meant to uphold this notion.

A very important original work and the earliest published by Cooke.

Cooke and Wheatstone and the Invention of the Electric Telegraph. By Geoffrey Hubbard, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London. June 1965. 158 pages, illustrated.

This 1965 work by author Geoffrey Hubbard is the first modern historical treatise on the electromagnetic telegraph and to this day stands as a landmark work.

The reason this book is important is because Hubbard went the extra mile and published the first ever references to the letters of William Fothergill Cooke to Latimer Clark that were in the holdings of the Institute of Electricians and Electrical Engineers in New York City.

These letters were actually formerly in the collection of Latimer Clark, an ardent co-founder of what today has become IEEE. Since transferred from IEEE to the New York City Public Library in the mid-1990's housed in the Rare Book Department there and actually hidden away to this day in an annex storage area, the Cooke letters to Clark may actual hold even more secrets about the development of the telegraph that have yet to be mined. These were letters written by Cooke to Clark later in his life, before he died.

Significantly, in these letters Cooke references Frederick Kerby, his machinist. Author Hubbard gives first ever reference to Kerby's mention on more than one occasion. It was these very references that helped historian Richard Warren Lipack establish the early authentication of the Cooke telegraph builder's manuscript journal.

Not withstanding, author Hubbard provides the first cohesive scholarly look at Cooke and Wheatstone's invention of the electric telegraph in a detailed manner and the exhaustive footnotes and agendum reference at the end of the book are the wholly substantial and in most cases even more significant for researchers than what is found in the main body of the book. For one seeking to understand the enormous puzzle that is the history behind the development of the electric telegraph in England and what it also meant on a world wide level, this book by Hubbard is a must.

Extracts From the Private Letters of Sir William Fothergill Cooke 1836-39 Relating to The Invention and Development of the Electric Telegraph. Edited by F. H. Webb, Secretary Inst. E. F. This 1895 first edition published by E. & F. N. Spon, London and New York reprinted 2010 - Kessinger Publishing, LLC. 95 pages, illustrated.